For thousands of years, wise men and prophets have warned us that greed, selfishness and arrogance were not good for us and that we should practice generosity, service and humility.

We didn’t believe them.

Moses said “Love thy neighbor as thyself.”

We ignored Him.

Jesus said “feed the hungry, clothe the naked and comfort the sick.”

We stuck our fingers in our ears.

Mohammed said “Woe betide every slanderer and defamer, him that layeth up riches and counteth them.”

We kept on counting our money.

All three of them told us not to charge interest on loans.[i]

We conveniently forgot.

Baha’u’llah[ii] said we should eliminate the extremes of wealth and poverty.

We never acknowledged His existence.

We thought that these were moral teachings designed to get us into heaven. We never dreamed that they were economic teachings designed to make the world function more smoothly. After all, what does God know about economics?

Actually, as it turns out, quite a bit.

You see, God designed the universe in such a way that moral behavior also makes the material world function more smoothly. When we follow God’s guidance, it doesn’t just get us into some future heaven, but it also helps build a kind of heaven right here on earth. Believe it or not, part of God’s plan is for us to have a healthy and stable global economy that can sustainably support the entire population with a comfortable standard of living! God wants the very best for us, and therefore the best is possible. If we follow God’s guidance, then that is what we will get. If we don’t … well, you can see how successful we have been by trying to do it the other way. Maybe now we are ready to learn the lessons the recent collapse has to teach us – starting with the need to eliminate the extremes of wealth and poverty.

From economic disparity to economic collapse

It would be easy to learn the wrong lessons from the recent collapse. Those who are too close to the problem see it in terms of housing bubbles and credit default swaps and all sorts of very specific financial instruments. Those who see the big picture accurately name the culprit as greed. Unfortunately, if the only lesson we learn is that people shouldn’t be greedy, we will not have gained any useful insights. A useful lesson needs to fall somewhere between the grand spiritual principle and the specific economic transactions.

Understanding the role that economic disparity played in the collapse – the ever widening gap between the rich and the poor – would give us useful insights that we could apply to personal, national and international policies. It would offer many points of intervention that could gently shift our policies and priorities in new, more healthy and more spiritual directions.

“But the principal cause of these difficulties lies in the laws of the present civilization; for they lead to a small number of individuals accumulating incomparable fortunes, beyond their needs, whilst the greater number remains destitute, stripped and in the greatest misery. This is contrary to justice, to humanity, to equity; it is the height of iniquity, the opposite to what causes divine satisfaction…

“It is, then, clear and evident that the repartition of excessive fortunes amongst a small number of individuals, while the masses are in misery, is an iniquity and an injustice. In the same way, absolute equality would be an obstacle to life, to welfare, to order and to the peace of humanity. In such a question a just medium is preferable. …” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions pg. 273

Up to here, I’ve told you what you already know – that economic disparity is not a good thing. You probably already believe this for moral reasons. Here is where I leave both religion and standard economic theory behind and try to figure out why economic disparity is bad for the economy. If you want the “usual” analysis then read the newspapers. If you want divine Truth, jump ahead to the appendix. But if you are curious about how the system got so far out of balance, I humbly offer you my own entirely personal opinion…

It is clear how economic disparity is a moral question, but how does economic disparity hurt the economy itself? To see the causal connection, we must first understand how a healthy economy works.

The Heartbeat of a Healthy Economy

What makes an economy healthy and self-sustaining? In a healthy economy, people produce goods and services, they are paid for producing them, and then they go out and buy different goods and services with the money they earn. That’s it. It really isn’t all that complicated.

One of the miraculous aspects of a healthy system is that it can chug along quite nicely without needing to grow or generate excess profits. This is important. It does not have to be driven by a 40-hour work week or constantly increasing consumption. If the needs of the community can be met in 20 hours, then it can stop producing. It doesn’t have to go on to produce twice what people need and then tell them to go buy more stuff. In the developed world, we don’t really need to consume more, but we may need to consume more wisely. There are still some parts of the world, however, in which more is still needed for basic survival. When efficiency and productivity gains provide this increase, then, in a healthy economy, that increase is reflected in wages so that those extra goods can be purchased. What makes an economy healthy is not its size or its growth, but the continuous circular flow of resources.

Excess wealth interrupts this natural flow of resources.

It is not necessary – or even desirable – for everyone in a healthy economy to be paid the same amount, just so long as everyone earns enough to get by, and everyone spends what they earn. The problems arise when a few people are allowed to make so much money that they can’t spend it all. When this happens, then this excess wealth is diverted away from the purchase of goods and services and put into savings instead. This diversion of resources disrupts the natural flow of money through the system, causing the economy to spiral downward. If goods go unsold, then the companies who hire workers won’t make enough money to pay their wages. Not only that, but these companies will have excess inventory and will have to cut back on production, so they won’t need as many workers. This will reinforce the downward spiral.

Now, before you go out and spend your retirement savings in order to rescue the economy, let me make a distinction between personal savings and excess wealth. Personal savings are what you use to send your kid to college, or set aside for a rainy day, or invest to prepare for retirement. It is not excess wealth, it is deferred consumption. It is money that you plan to spend – just not today. If everyone were paid equitably, there would be enough legitimate savings in the system to finance needed ventures. Excess wealth, on the other hand, is money that will never be spent. It is gathered and increased for reasons of status or power or pride. It will be passed on from generation to generation and never reenter the normal flow of commerce. It is this constantly increasing pool of excess resources that eventually overwhelms the financial system.

This excess wealth is money that the rest of us don’t even realize exists. It is hard for us to imagine that there is a surplus of savings when we are constantly told that Americans don’t save. Most Americans – indeed most people around the world do not have enough disposable income to save enough to cause even a blip in the flow of the economy. But a few Americans, and a small number of others do have enough savings to disrupt the natural flow of the economy. One of the places that people store their excess wealth, for example, is in stocks. Before the last market crash, Americans had taken over 17 trillion dollars of their savings (150% of our annual GDP) and bought stocks. Of that, the richest 10 percent of American families owned about 85 percent of all outstanding stocks. In addition, they also owned about 85 percent of all financial securities, and 90 percent of all business assets. This means that 85-90% of the savings in the US were accumulated by just 10% of the population. This shows that a significant portion of our nation’s wealth is tied up in savings, and that it is mostly controlled by a very few people. This represents money that is not available to be used to purchase cars, food, clothing, education, medical care or any other part of the real economy. No wonder our economy is struggling. No matter how much the bottom 90% of the population tries to spend, they don’t have a chance of compensating for the 85% of the savings that are pulled out of the system by the rich. On a global scale, according to analysis by Credit Suisse, just one percent of the global population owns around half of the world’s wealth. Clearly, the 1% cannot actually spend all of that wealth on consumer goods, no matter how many shoes and yachts they buy.

This is obvious. Anyone can see this. So why isn’t anyone doing something about it? Because everyone “knows” that as long as all of that saved money is invested – that is, if people use their excess money to generate even more money– then it goes back into the system as though it were being spent. In other words, people believe that using money is the same as spending money.

It isn’t.

Why Can’t Investment Compensate for Savings?

There are three primary ways to invest savings – Capital Investment, Loans, and the Stock Market. Each of these is a valuable tool for economic development under the proper circumstances. When the amount invested exceeds the economy’s actual needs, however, then each of them can cause more harm than good. Even the best of things turn bad when they pass the bounds of moderation.[iii]

Only a few economists[iv] acknowledge the dangers of having too much to invest, so let me explain why each of these investment tools ceases to be beneficial when investment exceeds need. Remember, the problem with savings is that it reduces the amount of money that is available to buy goods, which reduces consumption and increases the excess supply of goods. For investments to compensate for these savings in a positive way, they have to help increase consumption, or decrease the over-supply of goods.

Capital Investment

A capital investment is when you spend money to buy equipment to increase productivity. In a healthy economy, this is a good thing. Perhaps that is why it has been allowed by every major religion. Islamic countries still use investments rather than loans to run their economies. In a healthy economy, when productivity increases, so do wages. Everyone comes out ahead. But in an unhealthy economy, the people who are making the capital investment feel they have a right to the majority of the profits generated by the increased productivity. This means that wages don’t increase along with productivity. More and more goods are produced, but fewer workers have enough money to buy them with. This just makes the problem worse, because if the supply of excess goods increases, then workers will be laid off to compensate.

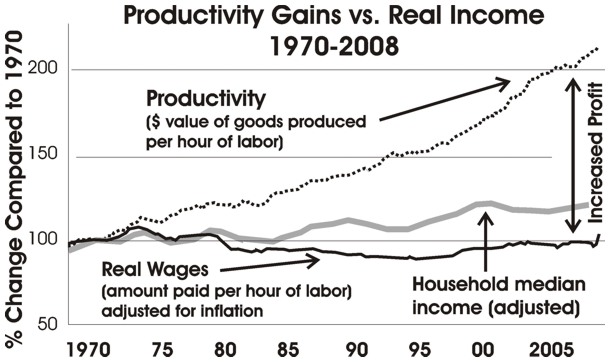

The economist who originally said that capital investments would compensate for savings modeled his theories on the kind of healthy economic spirit enunciated by Henry Ford: “There is one rule for the industrialist and that is: Make the best quality of goods possible at the lowest cost possible, paying the highest wages possible.” Unfortunately, that spirit no longer dominates business. Since 1975, the rise in America’s GDP (a measure of everything we produce) has been decoupled from rises wages. In other words, we all have produced more, but haven’t gotten paid accordingly. Between 2001 and 2006, for example, productivity in America soared by 16% per worker, while real median wages dropped by 2.9%.[v]

Today’s economists know this, but they haven’t reformulated their theories accordingly. In today’s economy – where the gap between the rich and poor continues to increase – using savings for capital investments only reduces wages and employment, and diverts more resources away from the healthy flow of the economy and into the hands of the rich.

Stocks

Related to capital investment is the purchase of stocks. If you buy new stock, then you are making a capital investment. In a healthy economy, in which the gains of investments are shared equitably, then the stock market is a reasonable way to pool resources and encourage capital investments. In an unhealthy economy, these capital investments create the problems I just described.

When there is too much money in the system, then there is no demand for new capital investments. This means that if you want to buy stock, you have to buy pre-existing stock. In this case, all you are doing is trading one person’s savings for another person’s savings. The terms stock exchange and trading stocks are accurate descriptions of what is going on. No consumption is taking place. It is like a bunch of kids getting together to trade baseball cards. They may be really excited about what great trades they made, but no new cards have been created or consumed. Very few people actually take money out of the stock market, so this money is not being used to buy goods or services. This means that the money sitting in the stock market might as well be stuffed under a mattress, for all the difference it makes in the greater economy. Whether stock prices are up or down, it does not change our ability to consume goods until such time as we actually sell our stock. (It can, however, change our perception of our ability to consume goods, and increase our willingness to borrow against our perceived wealth.) People selling stock without buying new stock are generally retirees who are part of the 90% of the population that only own 15% of the stock.

Loans

The third way in which the wealthy use their savings to make more money is through loans. This is potentially the most dangerous and destructive way to use excess savings. Judaism, Christianity and Islam all forbid charging interest on loans. The Bahá’í Faith allows interest, but Bahá’u’lláh admonishes us to show moderation, fairness, justice, tender mercy and compassion towards each other when giving loans.[vi] When there is no moderation in the distribution of wealth, then it is impossible to have moderation when that wealth is loaned out.

It is easy to see why. As the amount that the wealthy have to loan out increases, the amount the poor have with which to pay off those loans shrinks at a compounded rate. There is an invisible line that, once crossed, tips the equilibrium of the economy into a cascading avalanche of bankruptcies, defaults and foreclosures. Since the poor often borrow money in order to repay borrowed money, the line is passed long before the first wave of delinquent payments appear.

If loaning more money than people are able to pay back is a problem, then interest compounds that problem. Interest charged on loans increases the gap between rich and poor because it hurts the economy twice – once when the savings are removed from the regular flow of commerce, and again when interest is removed and added to those savings.

Economists say that when savings are loaned back into the economy, they allow people to buy more goods and keep the economy moving. It takes a calculated blindness to believe that a loan and a paycheck will have the same effect on the health of the economy. A loan allows you to buy today with tomorrow’s income, but when tomorrow comes, you will have to pay back both the money and the interest. In the long run, you will end up buying less. This means that if the economy needs consumers to buy more goods, they need to be paid more, not loaned more. But this is not what has happened. As the gap between wages and productivity has risen over the last 30 years, we have been encouraged to make up the difference by going deeper and deeper into debt. What the right hand took away in wages, the left hand returned in loans so that we never realized just how out-of-balance the system was. The long-term consequences were as predictable as they were catastrophic.

Until recently, consumer loans appeared to be a limitless source of free money for the rich. Bankers’ attitude towards plowing excess wealth into consumer debt in order to make a profit seems to have been the same as polluters’ attitude towards putting excess garbage into the ocean: “There is always room for more.” Well, as we’ve discovered, there isn’t.

Though the rich seemed to have a limitless supply of money to lend, there was clearly an upper limit to the amount that the middle class could borrow before they became unable to pay off their loans. For every dollar loaned, there had to be a dollar borrowed. Once a person owes more than they can possibly pay off without sacrificing their health or giving up their first-born child, then they give up and walk away from the loan. This is why the sub-prime mortgage market collapsed. The rich wanted to make money by loaning to the middle class — forgetting that they had already milked them of any ability to pay their debts.

There is an old saying: If I loan you $100, that’s your problem. If I loan you a million, that’s MY problem. The rich finally loaned more than they could afford to lose. Instead of accepting that they had been unwise, they blamed the borrowers and came to the government for a bail-out. Not only did they not learn their lesson, but they are actively working to stop laws that would prevent the same mistakes from happening again.

Business loans are a different situation. Business loans at reasonable interest rates are a legitimate way to finance capital investments if they will generate enough profit to compensate for the interest. Nevertheless, as loans, they suffer the same shortcomings as consumer loans when it comes to putting money back into the economy. They have to be repaid with interest, so the net effect is a decrease in the money available to the borrower for purchases. In addition, loans put into capital improvements create the same problems as any other capital investment if productivity gains are not shared with workers.

Dealing with the Excess

From this quick analysis, we can see that while it is useful to have a moderate amount of excess wealth available to invest, there is a limit to the amount of excess that the economy can absorb. This simple statement points to a fundamental dilemma. If there is more excess wealth in the system than the economy can safely absorb, what do you do with what is left? Trying to answer that question in a way that puts even more excess wealth in the hands of the already wealthy is what led investors into increasingly risky and sometimes illegal schemes. As Branko Milanovic of the World Bank said:

“Overwhelmed with such an amount of funds, and short of good opportunities to invest the capital as well as enticed by large fees attending each transaction, the financial sector became more and more reckless, basically throwing money at anyone who would take it.”[vii]

So if there is no good way to invest this excess wealth, the only logical solution is to find a way to reduce it. In other words, if the rich have more than they can safely use or invest, then for their own sakes and ours, we must find a way to get that excess into the hands of people who can use it effectively – that is, the poor and middle class.

The long-term solution to the world’s economic cycle of boom and bust, then, is to work to reduce the disparity between the rich and poor. This can be done through policies that help increase wages, share profits, and limit or tax excess accumulation of wealth. Five years after the collapse, the International Monetary Fund is finally realizing the truth of this. Let’s hope that they follow through on their own newly-discovered insights.

When matters will be thus fixed, the owner of the factory will no longer put aside daily a treasure which he has absolutely no need of (for, if the fortune is disproportionate, the capitalist succumbs under a formidable burden and gets into the greatest difficulties and troubles; the administration of an excessive fortune is very difficult and exhausts man’s natural strength). And the workmen and artisans will no longer be in the greatest misery and want; they will no longer be submitted to the worst privations at the end of their life.(Abdu’l-Baha, Some Answered Questions, p. 274-278)

There is, of course, great resistance to this solution from the wealthy who feel that they deserve all they have and more.

The Moral Hazards of Wealth

Most people are aware of what Jesus says about the dangers of being rich: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.”

The “eye of the needle” was what they called the small door within the larger gate to a city. Once the gate to a city was closed, a traveler could still get in, but his camel would have to crawl through on its knees – showing humility – in order to enter. This means that the rich are welcome in heaven – but only if they are willing to let go of arrogance and show some humility.

Bahá’u’lláh says something similar: “The rich, but for a few, shall in no wise attain the court of His presence nor enter the city of content and resignation.” But He goes on to say, “Well is it then with him, who, being rich, is not hindered by his riches from the eternal kingdom….” This means it is not wealth itself that gets us into trouble, it is something about our response to being wealthy. Without pointing fingers at anyone in specific, I would like to explore what is it about having wealth that makes it difficult for some people to also have humility.

When people become too wealthy, they often try to make sense of their enormously good luck by convincing themselves that they must somehow deserve to be rich, and that others, obviously, do not. It is much easier to look at a poor person and see how they are receiving handouts and entitlements than it is to recognize the silver spoon that some are handed at birth. Money is like a lever. The same amount of effort creates a hundred times more results. When rich people see the results of their efforts, they can’t help but think it is their effort, their brilliance, their talents that generated all of their wealth, when in reality it was the leverage created by their money. They can’t see that millions of others might have done even greater things – if they had only had the chance to use the magical leverage of wealth.

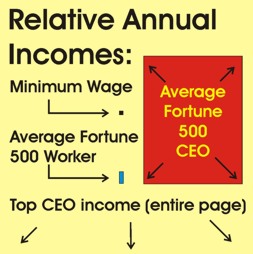

None of us can truly imagine what we might accomplish if our circumstances were different, so we can’t blame the wealthy if they have an irrational belief that their efforts are worth, not two, not ten, but hundreds or thousands of times more reward than the efforts of those who work for them. This is why the CEO’s of companies in the U.S. feel that they deserve to make 261 times the wage of the average worker, and 812 times the minimum wage. One famous CEO once made 36,000 times more than his lowest paid workers. I’m sure he was brilliant. But was he 36,000 times more brilliant than everyone else? Not even Einstein was that smart.

What the ultra-rich find difficult to understand is that it is physically impossible for one person to generate a million dollars in wealth without the assistance of hundreds, or even thousands of other people’s labor. No matter how wonderful one person’s ideas are, or how creative or talented they are, or what wizards of finance they may be, it takes an entire infrastructure in order to bring these ideas, talents or transactions into existence. Each person in that chain is deserving of a share of the wealth. Each person is a soul with needs, dreams and capacities. The irrational conviction that one’s own life is inherently worth more than the lives of these thousands of others is spiritually deadly. It is what allows one person to live in a mansion while surrounded by the starving and homeless. It threatens to destroy the very qualities of compassion and empathy that make us human.

“It is the animal proclivity to look after one’s own comfort. But man was created to be a man — to be fair, to be just, to be merciful, to be kind to all his species, never to be willing that he himself be well off while others are in misery and distress — this is an attribute of the animal and not of man.” – ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Foundations of World Unity pg. 42

The simple fact is that the rich don’t need all that they have. If they did, they would spend it and we wouldn’t be in this mess. It is the need for power, fame and the intangibles that money bring that cause people to hoard a thousand times a King’s ransom. If these same people were motivated by intangibles like love, service, honor, compassion, and justice, then the world would be a different place.

Spiritual Solutions to the Economic Problem

The world’s religions told us not to be greedy, not to hoard money, not to charge exorbitant interest, and not to let the gap between rich and poor become extreme. We ignored them, and now our economy is in the worst crisis it has faced since the last time the gap between rich and poor became this big. It is clear that God knows more about running the economy than we do. In light of this fact, can we turn to religion to give us insights as to how to get ourselves back out of this mess?

As we’ve discovered, religious teachings that appear to be strictly spiritual in nature often turn out to have significant economic impact. We could therefore suggest that every word of scripture from every religion probably contains within it the seed of a solution to our problems – from “Do unto others,” to “Noble have I created thee.” As a believer in all of the world’s great religions, I would like to highlight a few spiritual principles that I believe are particularly applicable to the current world situation. Please keep in mind that these observations are my extrapolations of the scriptures quoted. Others might come to a different conclusion.

World Citizenship and the Oneness of Humanity

“The earth is but one country and mankind its citizens.” – Bahá’u’lláh

“The world of humanity is one and God is equally kind to all.”[viii] ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

These simple principles imply a whole new approach to understanding our economy. First, they recognize that the world’s economy is a closed system. Economic theories that treat the economy as an open system; that rely on the exploitation of people or resources from “outside” the system; that assume an unending supply of resources; that depend on unsustainable growth – all have to be abandoned in favor of a single integrated system.

Second, they point us towards the development of a world currency and global standards of banking and finance.

Most important, they call for a whole new way of seeing ourselves as members of one human family – cooperating and communicating in a way that leaves no one out. We are truly all in this together.

Service to Humanity is Worship to God

When Jesus said “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me,” He was setting a standard that was about more than feeding the hungry or clothing the naked. He was saying that service of any kind that makes human existence better is service to God and a form of worship. Bahá’u’lláh is even more direct when He says “It is enjoined upon every one of you to engage in some form of occupation, such as crafts, trades and the like. We have graciously exalted your engagement in such work to the rank of worship unto God, the True One.” (Baha’u’llah, Tablets of Baha’u’llah, p. 26)

This perspective offers an alternative to greed and competition as the motivating force behind economic progress. It elevates the station of the lowliest worker, while calling into question the role of those who make a lot of money, but do not make the world a better place.

Economic Justice

While economic justice is an implicit extension of the Golden Rule, which is reiterated in every major religion, only the Bahá’í Faith offers specific policy guidelines for organizing a just society.

Progressive taxation is clearly enunciated as a principle – not just as a way to generate revenue for the funding of public works projects, but specifically as a way to moderate the extremes in income.

“All must be producers. Each person in the community whose income is equal to his individual producing capacity shall be exempt from taxation. But if his income is greater than his needs he must pay a tax until an adjustment is effected. That is to say, a man’s capacity for production and his needs will be equalized and reconciled through taxation.” (Abdu’l-Baha, Foundations of World Unity, p. 37)

There is a fear, expressed by some, that by increasing taxes on the ultra rich the economy will somehow be hurt. They say there won’t be enough money available for investments, or the wealthy will stop working because they won’t make enough money. The answer to this is three-fold. First, history does not support this claim. The top tax rate in the U.S.is currently[ix] 35%, with a proposed increase to 38%. During the 1950’s – a time of great growth and prosperity – it was 91%. This did not hurt the economy at all. There was still plenty of money available for wise and productive investments. Second, it is an excess of investment wealth that enabled the reckless investments that caused the recent crash. Reducing it would be a good thing. Third, if the people who have more wealth than they are able to spend were to decide to retire early in order to pay less taxes, then that would just free up more jobs for the millions of unemployed. If, for the wealthy, work is not considered a form of worship, then perhaps the economy would do just as well without them. After all, no one is indispensable.

Profit sharing is also highly praised in the Bahá’í writings – both as a way to equalize wealth, and as a way to encourage cooperation between capital and labor – giving workers a stake in their efforts.

“The owners of properties, mines and factories, should share their incomes with their employees, and give a fairly certain percentage of their profits to their workingmen, in order that the employees should receive, besides their wages, some of the general income of the factory, so that the employee may strive with his soul in the work.” (Dr. J.E. Esslemont, Baha’u’llah and the New Era, p. 146 – quoting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in NH 1912))

Fair wages are specifically called for. Though the term “minimum wage” does not appear in the Bahá’í writings, it would be in keeping with the principle of justice to raise the minimum wage to one that could support a small family.

Since no Holy Scripture is so detailed as to address the specific economic situation we are facing today, the following observations are just my personal musings:

Most of the solutions being sought today seem to be about “freeing up the credit market” or “getting credit flowing again.” To me, this sounds like getting rid of an alcoholic’s headache by giving him easier access to the tap. It only pushes the problem further into the future, when it will hit back twice as hard. We already have too many loans and not enough wages to pay them back. The problem isn’t that there isn’t enough money to loan, but rather there are too few people (or institutions) who are worth the risk. Making it easier to borrow only tempts people to make poor decisions. The solution is to get higher wages, not more debt, into the hands of ordinary people who will spend them on goods and services that will get the economy flowing again.

Because my Faith puts an emphasis on both work and education, values science and respects the environment, I would like to see money go into wages for workers in education, research and renewable energy, as well as infrastructure and mass transit. Wages for these valuable projects should be generated through higher taxes, not more debt.

Other than spending money for the public good, I believe that the fastest way to get the economy in balance again would be to reduce interest rates on existing loans, and forgive or drastically reduce the principle due on mortgages and credit card debt. While many might consider this extreme, it is no more extreme than forgiving an entire country’s debt, or handing trillions of dollars to the wealthy so they can pay for their unwise financial gambles, or letting both corporations and individuals go bankrupt. When an individual goes bankrupt, all debts are wiped out, even those he or she might be able to pay. This creates unneeded stress on other lenders. The individual also usually loses his house, which is a stress on the entire community. Reducing principle owed would do the least damage while allowing the individual to retain his dignity and strive to behave responsibly in the future.

The principle of forgiving debt goes all the way back to the Jewish law of the Jubilee. While the Jewish law is no longer practiced, the principle of forgiving the debts of those unable to pay them has been applied by many cultures for thousands of years.

“At the end of every seven years thou shalt make a release. And this is the manner of the release: Every creditor that lendeth ought unto his neighbour shall release it; he shall not exact it of his neighbour, or of his brother; because it is called the LORD’s release… Save when there shall be no poor among you…” (Deuteronomy15:1-4)

I look forward to the day when there will be no poor among us.

Spiritual Transformation

Ultimately, changing policies, tax structure, minimum wages, forgiving debt and the like will not be enough. As a nation and as a world we need to completely reorient our attitude towards the material world. The poor and middle class are just as addicted to consumerism as the rich are addicted to wealth and power. No one is innocent. Everyone contributed to the collapse. If we don’t want to see the cycle repeat itself generation after generation, we need to change our priorities, recognize our interdependence, work towards sustainability, acknowledge intangible forms of wealth, and generally start caring a whole lot more about one another. When the world is spiritually out of balance, how can we possible expect it to be in balance economically?

In order to understand the economy, we had to step back from the specifics of the current collapse. To truly solve our economic problems we have to step back even further. We have to take a God’s-eye view of life and the world in order to remember what is really important, and how everything fits together in one beautiful, interconnected whole.

The work we do in service to others is the path we walk on our way to God. The wealth we receive in return is both the reward for our efforts and a tool for future service. This wealth consists of more than just money. It includes all of the lessons we learn, the virtues we develop and the relationships we build. No matter what happens to the material economy, no one can take away our true wealth. We carry it with us wherever we go, and it will carry us through whatever troubled times lie ahead.

If we learn these lessons – even if we learn them the hard way – then the economic collapse will have been a blessing in disguise.

Appendix

Here are just a few relevant quotations from the world’s great religions:

Ensnared In nooses of a hundred idle hopes, Slaves to their passion and their wrath, they buy Wealth with base deeds, to glut hot appetites…. (Hindu, Bhagavad Gita (Edwin Arnold tr))

Craving for wealth, the foolish man ruins himself by destroying others. (Buddhist, Dhammapada – Sayings of the Buddha 3 (tr. J. Richards))

So Moses went back to the LORD and said, “Oh, what a great sin these people have committed! They have made themselves gods of gold. Exodus 32:31

Ecclesiastes 2:26 To the man who pleases him, God gives wisdom, knowledge and happiness, but to the sinner he gives the task of gathering and storing up wealth to hand it over to the one who pleases God. This too is meaningless, a chasing after the wind.

Matthew 6 19- Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal: But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal: For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.

Luke16:11 So if you have not been trustworthy in handling worldly wealth, who will trust you with true riches?

Quran 2:195 Spend your wealth for the cause of God, and be not cast by your own hands to ruin; and do good. Lo! God loveth the beneficent.

The beginning of magnanimity is when man expendeth his wealth on himself, on his family and on the poor among his brethren in his Faith. (Baha’u’llah, Tablets of Baha’u’llah, p. 156)

49. O CHILDREN OF DUST! Tell the rich of themidnightsighing of the poor, lest heedlessness lead them into the path of destruction, and deprive them of the Tree of Wealth. To give and to be generous are attributes of Mine; well is it with him that adorneth himself with My virtues. (Baha’u’llah, The Persian Hidden Words)

Detachment does not consist in setting fire to one’s house, or becoming bankrupt or throwing one’s fortune out of the window, or even giving away all of one’s possessions. Detachment consists in refraining from letting our possessions possess us. Abdu’l-Baha, Divine Philosophy, p. 135

Wealth is most commendable, provided the entire population is wealthy. If, however, a few have inordinate riches while the rest are impoverished, and no fruit or benefit accrues from that wealth, then it is only a liability to its possessor. If, on the other hand, it is expended for the promotion of knowledge, the founding of elementary and other schools, the encouragement of art and industry, the training of orphans and the poor – in brief, if it is dedicated to the welfare of society – its possessor will stand out before God and man as the most excellent of all who live on earth and will be accounted as one of the people of paradise. (Abdu’l-Baha, The Secret of Divine Civilization, p. 24)

Then rules and laws should be established to regulate the excessive fortunes of certain private individuals and meet the needs of millions of the poor masses; thus a certain moderation would be obtained. However, absolute equality is just as impossible, for absolute equality in fortunes, honors, commerce, agriculture, industry would end in disorderliness, in chaos, in disorganization of the means of existence, and in universal disappointment: the order of the community would be quite destroyed. Thus difficulties will also arise when unjustified equality is imposed. It is, therefore, preferable for moderation to be established by means of laws and regulations to hinder the constitution of the excessive fortunes of certain individuals, and to protect the essential needs of the masses. For instance, the manufacturers and the industrialists heap up a treasure each day, and the poor artisans do not gain their daily sustenance: that is the height of iniquity, and no just man can accept it. Therefore, laws and regulations should be established which would permit the workmen to receive from the factory owner their wages and a share in the fourth or the fifth part of the profits, according to the capacity of the factory; or in some other way the body of workmen and the manufacturers should share equitably the profits and advantages. Indeed, the capital and management come from the owner of the factory, and the work and labor, from the body of the workmen. Either the workmen should receive wages which assure them an adequate support and, when they cease work, becoming feeble or helpless, they should have sufficient benefits from the income of the industry; or the wages should be high enough to satisfy the workmen with the amount they receive so that they may themselves be able to put a little aside for days of want and helplessness.

When matters will be thus fixed, the owner of the factory will no longer put aside daily a treasure which he has absolutely no need of (for, if the fortune is disproportionate, the capitalist succumbs under a formidable burden and gets into the greatest difficulties and troubles; the administration of an excessive fortune is very difficult and exhausts man’s natural strength). And the workmen and artisans will no longer be in the greatest misery and want; they will no longer be submitted to the worst privations at the end of their life.

It is, then, clear and evident that the repartition of excessive fortunes among a small number of individuals, while the masses are in need, is an iniquity and an injustice. In the same way, absolute equality would be an obstacle to life, to welfare, to order and to the peace of humanity. In such a question moderation is preferable. It lies in the capitalists’ being moderate in the acquisition of their profits, and in their having a consideration for the welfare of the poor and needy — that is to say, that the workmen and artisans receive a fixed and established daily wage — and have a share in the general profits of the factory.

It would be well, with regard to the common rights of manufacturers, workmen and artisans, that laws be established, giving moderate profits to manufacturers, and to workmen the necessary means of existence and security for the future. Thus when they become feeble and cease working, get old and helpless, or leave behind children under age, they and their children will not be annihilated by excess of poverty. And it is from the income of the factory itself, to which they have a right, that they will derive a share, however small, toward their livelihood.

…Good God! Is it possible that, seeing one of his fellow-creatures starving, destitute of everything, a man can rest and live comfortably in his luxurious mansion? He who meets another in the greatest misery, can he enjoy his fortune? That is why, in the Religion of God, it is prescribed and established that wealthy men each year give over a certain part of their fortune for the maintenance of the poor and unfortunate. That is the foundation of the Religion of God and is binding upon all. (Abdu’l-Baha, Some Answered Questions, p. 274-278)

[i] You shall not charge interest to your brother — interest on money or food or anything that is lent out at interest. To a foreigner you may charge interest, but to your brother you shall not charge interest, that the LORD your God may bless you in all to which you set your hand in the land which you are entering to possess. (Deuteronomy 23:19,20)

[ii] The Prophet-Founder of the Bahá’í Faith – 1817-1892.

[iii] “If carried to excess, civilization will prove as prolific a source of evil as it had been of goodness when kept within the restraints of moderation.” (Baha’u’llah, Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah, p. 342)

[iv] For more on this, see Revenge of the Savings Glut, an editorial by Paul Krugman, NY Times, March 2 2009, and The Global Saving Glut and the U.S. Current Account Deficit, a talk by Ben Bernanke, March 2005. and Economy: Root of the Crisis by Branko Milanovic of the World Bank, DailyTimes.com May 7 2009

[v] Lane Kenworthy – Professor of Sociology and Political Science, University of Arizona Weblog “Slow Income Growth for Middle America” September 3, 2008

[vi] Therefore as a token of favour towards men We have prescribed that interest on money should be treated like other business transactions that are current amongst men.

…However, this is a matter that should be practised with moderation and fairness. Our Pen of Glory hath, as a token of wisdom and for the convenience of the people, desisted from laying down its limit. Nevertheless We exhort the loved ones of God to observe justice and fairness, and to do that which would prompt the friends of God to evince tender mercy and compassion towards each other. Tablets of Baha’u’llah, p. 134

[vii] Economy: Root of the Crisis by Branko Milanovic of the World Bank, DailyTimes.com May 7 2009

[viii] (Abdu’l-Baha, Foundations of World Unity, p. 81)

[ix] Spring 2009

I’m thankful for the clarity you expressed in this article. It made understanding of taxation, capital investments, stocks and loans much easier. Thank you.